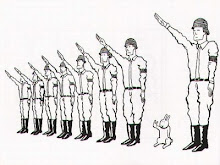

Charity

You've beautifully and righteously vented on something that's bothered me most of my life -- the distinct lack of charity in a lot of "charity." I've never sorted toy donations, but I've done canned food drives, and clothing donations, and at some point I always end up mumbling to myself, "Exactly when did you people come to the conclusion that the poor aren't human?" The one donation to clothing drives that sends me round the bend is torn underwear. What kind of people think the poor are so desperate they'd wear someone else's old underwear? And are they sitting at home basking in the warm glow of their generosity? Sorry -- charity drives bring out my most uncharitable side. And bad memories as well.I have to admit, this is partly a personal issue. I went through a period as kid when Christmas was ruined every year by the guy from the church (not our church, some other damn church) pulling up in a station wagon loaded with food boxes. My mother was too polite to turn him away.It started when I was eleven -- just old enough to begin reading adult body language. A man with a crew cut, wearing a bright red cardigan, carried a cardboard box into the apartment and set it on the kitchen table. My mother was in her robe, her hair in curlers, getting ready for work. She worked night shift. I could tell that she was in hurry and embarrassed to be seen like that, and that she wanted the man out of the apartment fast. But he hung around, asking stupid questions and glancing at everything out of the corner of his eye. I remember realizing that my mother was trying to maneuver to get him with his back to the couch, because the couch had a spring sticking out. She had covered it with a towel, but you could still see the outline of the spring, and the towel looked ratty anyway. Every poor person fixates on one thing that makes them feel especially poor, an objective correlative of poverty, and for my mother it was that sofa. She could buy her clothes at Goodwill and go without food at least once a week, she could handle being awakened by phone calls about my father's gambling debts, but somehow she felt less poor if she thought no one saw the sofa. My mother was from Ireland. I once read that during the potato famine, Irish peasants who realized they were about to die would find a corner of the houses that couldn't be seen from the window, and huddle there to wait for the end, humiliated by their starvation. And, strangely, I smiled when I read that sad detail, because it reminded me of my mother. You're all right as long as no one sees.The man in the red cardigan just didn't get it. He hung around chatting, as if he were waiting for something. And eventually my mother figured out what he wanted and gave it to him. She asked if he had a lot more deliveries to make. I think she was just trying to remind him to get going, but that question turned out to be exactly what he wanted. He started rambling on and on about how many people his church helped at this time of year and how proud he was of all those fine people, and how good it made him feel to help. My mother kept looking at the door. And then he said that what he had in the car was for the people in our building, and he looked at a piece of paper and told my mother which other apartments he was spreading his Christmas cheer to.Kids who grow up in violent homes learn to pick up the exact moment an adult becomes angry -- before they do anything. When the man named the other charity cases in the building, I could see a change in my mother's expression that I'm sure the man couldn't see. She kept smiling, but anger was building under the surface, made worse by the fact that she had to keep smiling and playing the part of the grateful poor lady. The anger came out after the man left. My mother screamed and cried that he was going to tell half the people in the building that she couldn't even feed her kid. And all the time she was jerking the curlers out of her hair, because priorities are priorities, and she was late for work. And anyway, she screamed, headed for the kitchen, that was a lie. A no-good lie. We always have food, except the day before payday, and we don't need their garbage. She took cans out of the box -- some dented, some labelless, others just useless. Beets, lard, hollandaise sauce. I remember looking at that little yellow can and wondering what it was. Did it come from Holland, and was it made of daisies? My mother picked up the small frozen turkey. "I don't want this garbage," she screamed -- and she threw the turkey to the floor, and stormed out of the kitchen. She'd thrown it so hard, it dented the linoleum.She left for work, and I put the canned charity away. There was one large box of kiddie cereal. The bottom of the box had gotten damp, and when I picked it up, it split open, and all the cereal scattered across the floor. Whenever I hear about welfare taking away people's dignity, I always remember crawling around on the kitchen floor, trying to pick up the sugary colored rings of private charity.I thought of the man who sucked the air out of Christmas a few days ago, as I was reading an article about President Bush urging Americans to give more to the needy. I'd second the idea, of course. It certainly wasn't his plea for time and money that bothered me. It was a president being photographed putting canned peaches and spinach in a bag, without thinking about the fact that there are more important and effective things he could do to help the needy. But of course that assumes that the point is to help those in need, and not to provide photo-ops for presidents, and chances for the middle class to feel good about themselves while getting rid of their garbage.

Labels: charity

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home