Less a threat than your bathtub

By John Mueller

WASHINGTON -- In a recent interview, Homeland Security czar Michael Chertoff thundered that the “struggle” against terrorism is a “significant existential” one -- carefully differentiating it, apparently, from all those insignificant existential struggles we have waged in the past.

Meanwhile, the New York Times assures us that “the fight against al-Qaida is the central battle for this generation,” and John McCain more expansively labels it the “transcendental challenge of the 21st century,” while Democrats routinely insist that the terrorist menace has been energized and much embellished by the war in Iraq.

It may be time to assess such strident and alarming proclamations about the threat terrorism presents to the United States. They hardly seem justified and are rather akin to Cold War concerns about the “threat” supposedly posed by domestic Communists, concerns that proved to be vastly exaggerated.

An excellent place to start is with analyses provided by Marc Sageman in lectures and in a recent book, “Leaderless Jihad.” Now a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, Sageman is a former intelligence officer with experience in Afghanistan. Carefully and systematically combing through both open and classified data on jihadists and would-be jihadists around the world, Sageman sorts al-Qaida -- just about the only terrorists who seem to want to target the United States itself -- into three groups.

First, there is a cluster left over from the struggles in Afghanistan against the Soviets in the 1980s. Currently they are huddled around, and hiding out with, Osama bin Laden somewhere in Afghanistan and/or Pakistan. This band, concludes Sageman, probably consists of a few dozen individuals. Joining them in the area is the second group: perhaps 100 fighters left over from al-Qaida’s golden days in Afghanistan in the 1990s.

These key portions of the enemy forces would total, then, less than 150 actual people. They may operate something resembling “training camps,” but these appear to be quite minor affairs. They also assist with the Taliban’s far larger and very troublesome insurgency in Afghanistan.

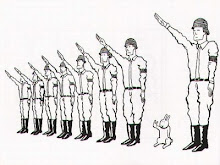

Beyond this tiny band, concludes Sageman, the third group consists of thousands of sympathizers and would-be jihadists spread around the globe who mainly connect in Internet chat rooms, engage in radicalizing conversations and variously dare each other actually to do something.

All of these rather hapless -- perhaps even pathetic -- people should of course be considered to be potentially dangerous. From time to time, they may be able to coalesce enough to carry out acts of terrorist violence, and policing efforts to stop them before they can do so are certainly justified. But the notion that they present an existential threat to just about anybody seems at least as fanciful as some of their schemes, and any notion that these characters could come up with nuclear weapons seems farfetched in the extreme.

The threat presented by these individuals is likely simply to fade away in time. Unless, of course, the United States overreacts and does something to enhance their numbers, prestige and determination -- something that is, needless to say, entirely possible.

I’ve checked this remarkable and decidedly unconventional evaluation of the threat with other prominent experts who have spent years studying the issue. They generally agree with Sageman.

One of them is Fawaz Gerges of Sarah Lawrence College, whose brilliant book, “The Far Enemy,” based on hundreds of interviews in the Middle East, parses the jihadist enterprise. As an additional concern, he suggests that Sageman’s third group may also include a small, but possibly growing, underclass of disaffected and hopeless young men in the Middle East, many of them scarcely literate, who, outraged at Israel and at America’s war in Iraq, may provide cannon fodder for the jihad. However, these people would mainly present problems in the Middle East (including in Iraq), not elsewhere.

Another way to evaluate the threat is to focus on the actual amount of violence perpetrated around the world by Muslim extremists since 9/11 outside of war zones. Included in the count would be terrorism of the much-publicized and fear-inducing sort that occurred in Bali in 2002; in Saudi Arabia, Morocco and Turkey in 2003; in the Philippines, Madrid and Egypt in 2004; and in London and Jordan in 2005.

Although these tallies make for grim reading, the total number of people killed comes to some 200 or 300 per year. That, of course, is 200 or 300 per year too many, but it hardly suggests that the perpetrators present a major threat, much less an existential one. For comparison: Over the same period, far more people have drowned in bathtubs in the United States alone.

An important reason for these low numbers, note Sageman and Gerges, is that policing agencies around the world, often working cooperatively, have rolled up, or rolled over, thousands of potential jihadist terrorists since 9/11. These include not only the police in Europe, but also in Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iran, Indonesia, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and Pakistan. They have been energized not out of any love for the United States, much less for its foreign policy, but because the terrorists threaten them as well. In addition, terrorist acts mostly tend to be counterproductive. Before some Jordanian hotels were bombed by terrorists, some 25 percent of Jordanians viewed bin Laden favorably. After the attacks, this fell to less than 1 percent.

Meanwhile, after years of well-funded sleuthing, the FBI and other investigative agencies have been unable to uncover a single true al-Qaida cell in the United States. Any “threat” appears, then, principally to derive from Sageman’s leaderless jihadists: self-selected people, often isolated from each other, who fantasize about performing impressive deeds.

From time to time, some of these characters may actually manage to do some damage, though in most cases their capacities and schemes -- or alleged schemes -- seem to be far less dire than initial press reports vividly, even hysterically, suggest. There is, for example, the diabolical would-be bomber of shopping malls in Rockford, Illinois, who exchanged two used stereo speakers for a bogus handgun and four equally bogus hand grenades supplied by an obliging FBI informant. Had the weapons been real, he might have caused harm, but he clearly posed no threat that was existential (significant or otherwise) to the United States, to Illinois, to Rockford, or, indeed, to the shopping mall.

If the “struggle” against enemies like that is our generation’s (or century’s) “central battle” or “transcendental challenge,” we are likely to come out quite well.

John Mueller is a professor of political science at Ohio State University. His most recent book, "Overblown," deals with exaggerations of security threats, particularly terrorism.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home