The Job Training Charade

By DON McINTOSH,

Reynolds Aluminum closes. Freightliner and Boeing lay off thousands. Consolidated Freightways goes out of business. Atofina Chemical. Pendleton Woolen Mills. Atlas Copco Wagner. Sawmills. Paper mills. In Oregon and Washington and across the country, good-paying unionized industrial jobs are vanishing rapidly, leaving hundreds of thousands to cope with unemployment in a recession that shows few signs of abating.

And what is the government's response? In previous eras, from the 1930s New Deal to the era of Jimmy Carter, when times were tough, the government stepped in as an employer of last resort, providing temporary jobs in public works, or simply providing people a subsidy to get by until they could recover.

But a new political orthodoxy has replaced that approach, says University of Oregon professor Gordon Lafer. Lafer, on staff of the U of O's Labor Education and Research Center and a longtime researcher in union campaigns, recently published a book criticizing the government's "job training fits all" approach to unemployment. Titled "The Job Training Charade," the book is the product of over a decade of research.

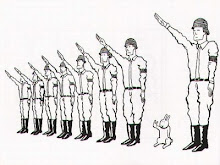

Lafer pulls few punches. He argues that the government's focus on job training is a political diversion, that government training programs have little or no effect on overall employment, and that workers are being trained for jobs that don't exist.

Lafer says job training programs focus attention on the supposed shortcomings of workers instead of the realities of an economic system that never produced enough jobs for everyone.

"Democrats kind of gave up the fight on unemployment. People on the right would say 'the problem with poor people is that they're lazy, and what you have to do is cut social benefits to force them back to work.' And the humane Democrats would say 'no, no, no, they really want to work, they just lack the skills,' so the pro-training position became the position of people with a heart. But what both of these have in common is deciding that one way or another, the explanation of poverty lies in the fault of workers themselves as opposed to anything you could fight in business or government policy."

The single biggest evaluation of the Job Training Partnership Act was done by the federal Department of Labor, which followed 20,000 people over four years and divided up the results by types of people and types of training. In three-quarters of the cases, they found no statistically significant impact whatsoever. For youth, ages 16 to 21, people who went through the program actually did worse than people who did not.

"Almost all federal job training programs for the last 20 years have been an almost complete and total failure," Lafer says, "and more importantly, the government and both political parties know that the programs are a failure, and keep funding them and promoting them anyway, because it's a kind of cheap political response to unemployment."

Their assumption, Lafer says, is that if only people had the skills, employers would hire them. "It's a kind of paradoxical thing: on average, people with more education are better paid, and for any individual, it may make sense. And so every parent wants that for their kid, but if you look at the country as a whole, the total percentage of American jobs that require a college degree is between 25 and 30 percent, and no economist thinks it's going to be more than that any time in our lifetimes. So the idea that if everybody got professional training, everybody would be earning professional wages is totally false."

And in fact, Lafer says, there are already lots of very highly-trained people who can't get decently-paid work.

"The number of jobs that are in the want ads is a tiny percentage of the number that need work. The labor market is like musical chairs: There are some jobs available, but the number of people who are in need of decently-paying jobs, over the period that I examined from 1984 to 1996, ranged between 7 to 1 and 20 to 1."

Ironically, many of the skills employers say they need aren't technical at all.

"You have employers all the time who say, 'the schools are failing us. The kids these days don't know how to work. And we can't get anyone with the right skills.' And you say 'well what exactly are the skills that you're missing?' Almost no employer mentions technical occupational skills, and very few mention English and math. What almost all of them talk about is discipline and punctuality, and attitude and work ethic."

Lafer says his answer is to ask how much they're paying, and he's not surprised to hear the biggest complaints about employability from the lowest-wage employers.

"Discipline and loyalty is not a 'skill' that you possess or don't possess," Lafer says. "It's something that you choose to give to a job or not depending on the wages and conditions that are offered. So when the government comes in and says 'we're going to train people to be disciplined to be employable,' what they're saying is 'we're going to train people to get used to the idea that they don't have any choice except to accept these low-wage jobs and not complain about it.'"

Ultimately, Lafer thinks, job training programs may serve as a diversion for workers victimized by the economic system, because they suggest the cause and solution of unemployment and poverty are fundamentally non-political.

Education and training play a role in determining wages, but Lafer says they account for less than one-third of wage differences. And the shift from manufacturing to service employment has been a shift toward jobs that require higher education even though they offer lower wages than the ones they replaced.

1 Comments:

At 2:41 PM, Anonymous said…

Anonymous said…

It bugs me that democrats are always portrayed as lazy and looking for a handout by the Repubs. Every low paid job I ever had was supervised by some lazy SOB that never pitched in no matter how busy we were and they were all Repubs.

Post a Comment

<< Home